Tuna School: Crash Course on a Local Delicacy

Perspectives | Jul 12, 2022

Atlantic bluefin tuna can present some challenges for seafood consumers looking for responsibly harvested options. These highly migratory fish are a complex species to manage, and that complexity sometimes gets lost in the public dialogue around the species. As part of our effort to provide some clarity around Atlantic bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Maine, we hosted local fishermen, dealers, chefs, and GMRI scientists for Tuna School, an educational (and tasty) part of our ongoing Trawl to Table series.

Eating sustainably can feel overwhelming, especially when it comes to seafood. Atlantic bluefin tuna can be a particular source of confusion, with contradicting reports surrounding its sustainability. These highly migratory fish might be complex — from how they are managed to their economics and unique biology — but in the Gulf of Maine, we have developed a scientific understanding that helps us feel more certain about this still somewhat mysterious species.

That’s why we hosted “Tuna School” as a part of our Trawl to Table Series. We updated restaurants on the sustainability of Atlantic bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Maine, advocated for increasing sales of this local fish, and dispelled myths for consumers. Our seafood specialists, Adam Baukus, Kyle Foley, and Sophie Scott brought together local fishermen, dealers, chefs, and GMRI scientists to break down all parts of the Atlantic bluefin tuna industry, and to put local Atlantic bluefin tuna in the spotlight of sustainable seafood in Maine.

What Does Sustainability Mean?

At GMRI, our work spreads across multiple disciplines, including scientists studying fish and the ecosystems they inhabit as well as resource economists and other experts collaborating to understand seafood markets. For us, sustainability means not only a healthy ocean ecosystem, but also the health of our marine economy and the communities that depend on those ecosystems. Kyle Foley, Senior Program Manager for the Sustainable Seafood team, works toward the community end by connecting all links in the seafood supply chain from fishermen to consumers.

“There is so much seafood and so many types of species we can be eating in the Gulf of Maine to have a positive impact on our coastal communities."

Kyle Foley Sustainable Seafood Director![]() Kyle Foley Sustainable Seafood Director

Kyle Foley Sustainable Seafood Director

Unfortunately, much of the seafood from our region has a tough time competing on a global scale; the U.S. imports ~90% of the seafood we eat, despite our wealth of local fisheries. The lobster and scallop fisheries get most of the buzz in Maine’s seafood industry, but the Gulf of Maine has plenty more to offer, such as Acadian redfish, Atlantic pollock, white hake, and, of course, Atlantic bluefin tuna.

The main reason we don’t see many of these fish on our plates is a lack of demand by markets and consumers. By partnering with local grocers, retailers, and culinary partners on their sustainability policies, we can help build demand and value for local seafood.

With science-informed fisheries strategies, we can continue to fish local stocks sustainably for years to come — and in the Gulf of Maine, management has become a leading example in sustainable fisheries. As Kyle explained to Tuna School participants, “It’s not the wild west. People can’t just hop in their boats anymore and do whatever they want.”

So, what can you do to help boost sustainable seafood in Maine? Eat, serve, and sell more local seafood. Support local markets by buying and preparing fish at home. Always ask your local grocers and restaurants where they source their seafood from, and let them know you want local!

The Tuna Management Success Story

Atlantic bluefin tuna has long been seen as the poster child for misunderstood seafood. As one of the largest, fastest open-ocean fish in the sea, these impressive animals have the ability to migrate astonishing distances quickly, which is part of what has made the species difficult to manage. After stocks plummeted in the late 1970s, this fish earned a reputation for being unsustainable — but with strict and smart management, population levels have rebounded to healthy levels in recent years.

Globally, there are three species of bluefin — Atlantic, Southern, and Pacific — and each species is managed separately. Atlantic bluefin tuna are the only species found in the Gulf of Maine; lucky for us, this also happens to be the most sustainably harvested bluefin tuna fishery in the world. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the Atlantic bluefin tuna is not currently overfished and populations are maintaining healthy levels.

In the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic bluefin are divided and managed as two stocks: the eastern stock, which includes adults that repeatedly spawn in the Mediterranean Sea, and the western stock that includes adults that spawn in and around the Gulf of Mexico. In the western Atlantic, three countries (Canada, Japan, and the U.S.) land almost 100% of the western Atlantic bluefin tuna quota. The National Marine Fisheries Service, with the Atlantic Migratory Species Management Division, domestically manages the U.S. Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) conducts stock assessments and allocates quotas to participating countries in line with science-based conservation and management recommendations. The National Marine Fisheries Service also allocates ICCAT quotas to different user groups (e.g., rod and reel, pelagic longline), sets minimum sizes, retention limits, and tracks commercial and recreational landings.

While we have plenty of Atlantic bluefin tuna here in the Gulf of Maine, the majority of bluefin tuna caught in the Atlantic are harvested from the Mediterranean Sea with large purse seines and longlines. These gear types make it possible for one vessel to catch many tuna at one time — but they also increase the likelihood of bycatch. In the U.S., almost all Atlantic bluefin tuna are caught by rod and reel, one at a time. This substantially reduces bycatch, and fishermen can maintain a higher quality catch.

The US has continually led conservation efforts for Atlantic bluefin tuna which includes the largest minimum commercial size in the world, ensuring that Atlantic bluefin tuna have a chance to grow and reproduce at least one time before being harvested. Add to that the “exceptional enforcement, monitoring, compliance and reporting,” and that the U.S. has one of the most sustainable bluefin tuna fisheries in the world, says GMRI Research Scientist and University of Maine Professor Dr. Walt Golet, who leads the Pelagic Fisheries Lab. “The U.S. has led and continues to lead with its nose on implementing conservation and management strategies.”

Overall, the status of the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery in the Gulf of Maine is healthy, says Dr. Golet. Unlike the still-struggling cod fishery, the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery has shown consistent recovery over the past decade, and the U.S. maintains excellent management strategies. With this in mind, Dr. Golet says we should feel good about seeing local Atlantic bluefin tuna on our menus.

Tuna Markets: A Global Commodity

Because of their exceptional taste and quality, Atlantic bluefin tuna has a reputation as one of the more valuable fish in the ocean. However, like other seafood, the value of Atlantic bluefin varies with demand, quality, and quantity. In 2021, commercial fishermen generated roughly $12 million in revenue from harvesting Atlantic bluefin tuna, which translated to an average $5/lb across the east coast. Historically, up to 90% of Atlantic bluefin from the U.S. east coast has been exported to Japan and other markets overseas. However, now only about 10% of Atlantic bluefin tuna caught in the Gulf of Maine are being exported to Japan — a major reversal.

In recent years, demand from overseas markets has dwindled for various reasons while, at the same time, Atlantic bluefin quotas and landings have increased in the U.S. This presents a real challenge for a local industry that does not have much local demand from consumers, and it has pushed prices to record low levels for fishermen.

Local restaurants and other businesses selling seafood have often been hesitant in the past to sell Atlantic bluefin because of its perceived sustainability issues. With the responsible regulations in place today for local Atlantic bluefin, businesses and consumers should feel comfortable and confident in purchasing this special fish.

Dr. Kanae Tokunaga, lead Research Scientist in our Coastal and Marine Economics Lab, studies these fluctuations and how they are impacted by climate change and socio-economic conditions. “Most years feature an early spike in landings which then trails off. This leads to harvesters being unable to sell their product. If we can smooth out landings to have a more consistent supply of Atlantic bluefin to the market, that would be even better for fishermen.”

The potential of this local fishery cannot be understated. Rather than shipping local Atlantic bluefin tuna around the world, which is incredibly costly and unreliable, we have an opportunity to keep the market local, generate more revenue for our fishing communities, and cut down both costs and carbon emissions.

From Boat to Plate

The quality of the tuna that ends up on your plate depends largely on some crucial steps that happen after the fish is caught. After tuna are brought on board, fishermen who are prioritizing quality will immediately bleed and clean the fish to remove the internal organs, which harbor bacteria and hold in heat, a process that maintains the freshness of the meat. Once the fish is cleaned, the entire body is covered with ice, and the body cavity is packed with ice as well, to bring down the body temperature. When the fish is offloaded from the boat, the head and tail are removed, and the body is sent to market to be graded.

At these markets, tunas are laid out to be inspected by world-class experts who can predict the quality of the meat simply by looking at the shape of the body, as well as the the color, texture, and fat content of the muscle. Most important is the quality of flesh with respect to meat color and fat content. Fish with good color and high fat content receive the highest grade and ex-vessel value.

After the tuna is purchased, it will be processed. There are over nine different cuts a single bluefin tuna can provide, and similarly to the red meat of a cow, these cuts vary in taste and can be used in an array of dishes. The toro is one of the most valuable cuts of meat and is found in the belly of the fish. This meat is rich and buttery, containing high amounts of fat. In fact, the fattier the meat, the higher quality it will be and the better it will taste. The cheek meat, also classified as toro, is highly desirable. Known as hoko-niku or kama-toro, this meat is a delicacy.

But there is so much more to tuna than toro, says Kelsey O’Connor, chief butcher for True Fin, a sustainable seafood business launched under our Gulf of Maine Ventures initiative that buys product directly from fishermen. O’Connor and Andrew Taylor of Big Tree Hospitality led a cutting demonstration of a freshly caught Atlantic bluefin tuna for Tuna School, highlighting the underutilized cuts of tuna.

The most common sushi cuts come from the top loins of the tuna and are typically lean and deep red in color. Once the upper and lower loins are removed, a substantial amount of meat can be carved from the skeleton by scraping the remaining meat off the bones for delicious tartar. In an effort to utilize every last part of the tuna, you can even cut the vertebrae out of the spine and slurp the spinal gel out. Jen Levin, President/CEO of True Fin, emphasizes that using all parts of the tuna is crucial to reduce waste — “I’ve made burgers with tuna mince, and it’s absolutely delicious.” Jen emphasizes just how much tuna Gulf of Maine waters hold, and how important it is that chefs and servers know where the fish they serve is caught, and how long ago it was caught.

After the demo, the group was treated to a delicious spread of tuna dishes prepared by chefs from Big Tree Hospitality, featuring sashimi, tartar, kabobs, and even vertebrae with spinal fluid.

Industry Perspectives

What better way to understand the local Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery than from two lifelong, Gulf of Maine, tuna fishermen? Bob Campbell of Chubbyfish, Inc., and Captain Pete Speeches, a fifth-generation tuna fisherman, led a panel discussion at Tuna School to share their expertise with the scientists, chefs, and others in attendance.

Campbell fished for Atlantic bluefin from the seventies to the nineties, when he became a dealer, buying tuna from fishermen and selling it to other distributors, processors, restaurants, and other customers. Now that Campbell works with fishermen rather than fishing himself, he recognizes the necessity of open communication between dealers and harvesters.

And when it comes to understanding just how sustainable the Atlantic bluefin fishery is? Simply look at the science, says Bob. “NOAA Fisheries just increased the quota — that doesn’t happen lightly. Every year, we hope something like this happens.” Decisions surrounding quota changes are driven by scientific data, and an increase in the quota limit is a clear indicator that Atlantic bluefin tuna populations are healthy and thriving.

As for Speeches, he’s seen it all in his forty years of fishing for Atlantic bluefin tuna. Today’s Gulf of Maine tuna fishery is drastically different than the one he knew years ago, from catching tuna one at a time, limiting fishermen to one fish per day, and other stricter management measures. He praised the strengthened connection between members of the supply chain. “It’s not just catching the fish and taking pictures for Facebook. It’s about helping the buyer. Helping my buyer helps me; it should be a symbiotic relationship.” He says we owe the current success of the fishery to this network of industry members: “If you’re around this fishery, you’ll see that these fish are everywhere and they’re not going extinct.”

The Science Behind the Management

The Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery doesn’t only include fishermen, buyers, and consumers. Scientists are also intricately linked to this industry. Despite the popularity of Atlantic bluefin tuna, questions like how fast they grow or how long they live still remain. Filling in these knowledge gaps is critical in maintaining the sustainability of the fishery — and scientists couldn’t answer these questions without the fishermen themselves.

Before Atlantic bluefin tuna are sold, their heads are removed since they are not often butchered for meat. Lucky for researchers, tuna heads are instrumental to researchers as they reveal mysteries about their complex biology. Dr. Golet has established a network with fishermen and dealers, extending down the entire length of the eastern coast of the U.S. He provides labels to fishermen, who are trained to identify sex and record the length of the fish, as well as the date and location it was caught. With just a head, Dr. Golet’s team can determine where the Atlantic bluefin tuna was spawned, how long they lived, how fast they were growing, and to what extent the eastern and western stocks are mixing with each other.

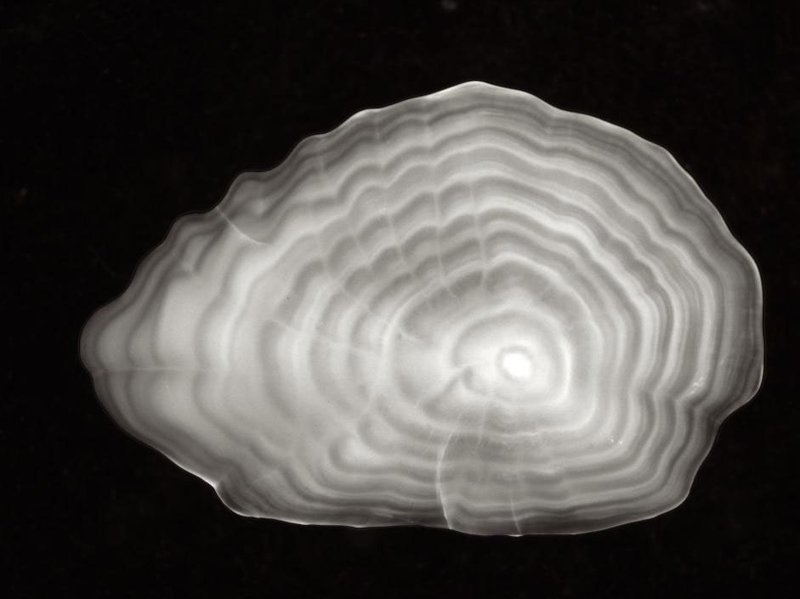

Among the most valuable parts of the tuna head are small "ear bones" known as otoliths, found at the base of the skull. These delicate crystalline structures, which help the tuna sense acceleration and maintain its orientation in the water column continue to grow over the course of a fish's life, and act like a data recorder. Specifically, they collect more material in the summer and less in the winter. This pattern forms alternating rings in the otolith — and, just like counting tree rings, these patterns can be used to determine how old the fish was when it was caught.

How old a fish gets is critical information for management, especially since Atlantic bluefin tuna longevity may extend beyond 40 years. This means they are relatively slow growing, which is all the more reason to keep a watchful eye on how many Atlantic bluefin tuna are harvested a year to avoid overfishing. These otoliths also have a unique chemical signature that can help scientists determine which side of the Atlantic the fish came from, which can help differentiate the eastern and western stocks, and inform us about the extent the two stocks mix year to year.

The otoliths aren’t the only scientific tool in the tuna heads: tissue samples can provide genetic clues. Imagine genealogy, but for fish. Researchers can actually match larvae to their parents. This information can aid in estimating the total number of Atlantic bluefin tuna in the western stock population, which is important in ensuring tuna stocks are at kept at sustainable levels.

This data collection is vital to the management of Atlantic bluefin tuna. The collaborative effort between scientists and all members of the supply chain makes it possible for such seamless work to occur. After all, members of this fishery are on the same side with one simple goal: keep the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery healthy and sustainable for years to come

An Easy Choice

It’s not every day that so many members of the Gulf of Maine Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery can gather and connect. “Tuna School” was a hit, and we were happy to provide a space for education, discussion, and networking. By continuing this unique dialogue between scientists, fishermen, restaurant owners, grocers, and others, we can ensure that we’ll have plenty of tuna to harvest in the future.

While making the right choice when it comes to sustainable seafood may seem complicated, supporting the Gulf of Maine Atlantic bluefin tuna industry is a simple choice that makes all the difference to your local economy. By eating, serving, and selling more local Atlantic bluefin tuna, we can all support a thriving and resilient local seafood system.